TL;DR: Not every AI product has a clear commercial purpose, but it should solve for some compelling user interest. We know this is the case when people have full information about what the experience is, what data it collects, and how it uses that data, and they still choose to opt-in (without the need of dark patterns and incentives).

Need a quick reference? ↓ Download the article guide, covering the range of needfulness in AI products and considerations when designing for each.

In the race to market, we’re already seeing a proliferation of flat out bad AI experiences hit consumers. A consistent thread I see connecting many of these are questions along the lines of, “who ever thought we needed this?”

Discord shut down its chatbot, Clyde last fall with no explanation, though user reviews hint at a horrendous experience that made the overall product worse. Google removed the ability for it’s AI, Gemini to create images after users found its “historically accurate” photos were anything but.

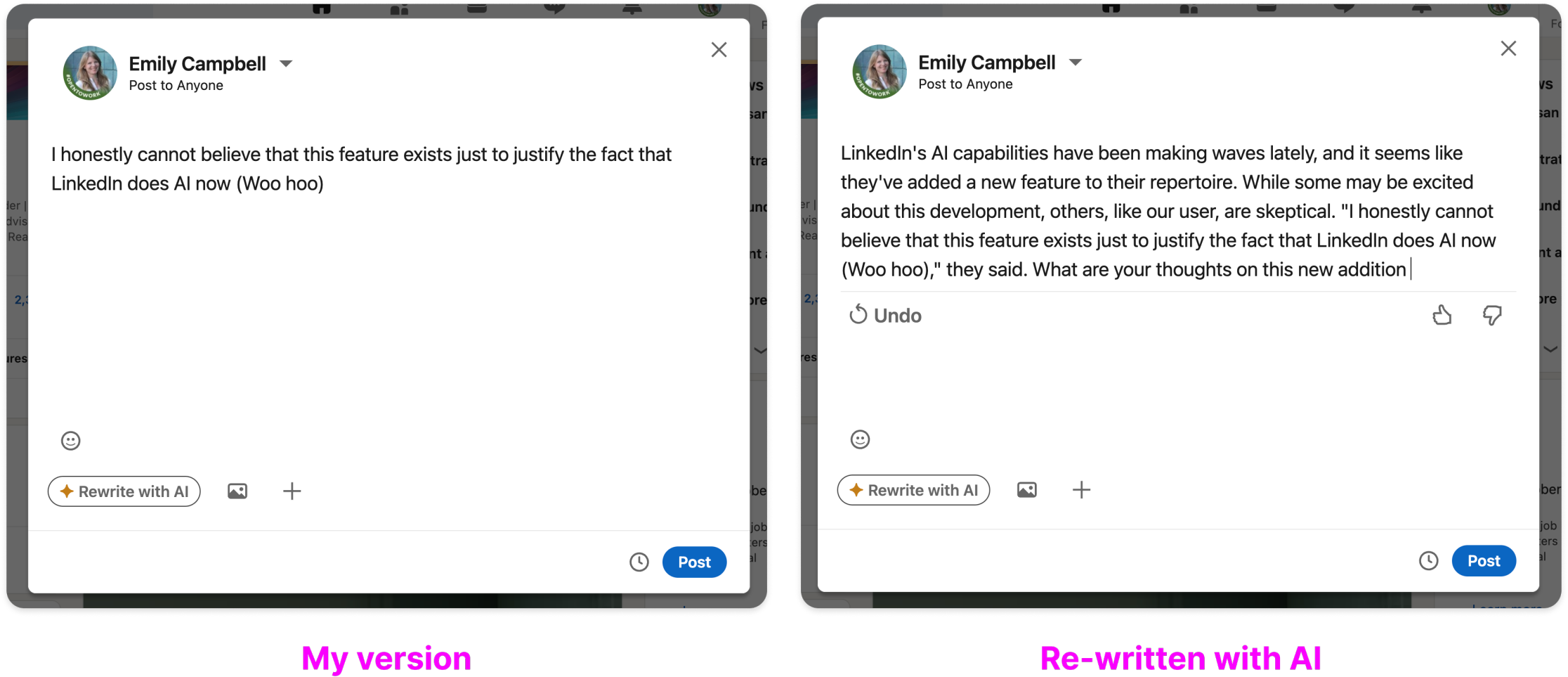

This isn’t limited to chatbots. LinkedIn’s Generative Articles are positioned as a way to let AI-crafted prompts drive human discussion, but in practice they are incentivizing users to game the system, or to contribute low-value responses to poorly-framed prompts. Don’t get me started on their text generation tools. Who needs this?

And this effect has spilled over into non-AI products. Philipp Temmel had a great piece recently in Creatively about the ways this surge of unnecessary and poorly crafted products has degraded platforms like Product Hunt.

It’s the natural next step to what Cory Doctorow coined “the enshitification of the web.”

When switching costs are high, services can be changed in ways that you dislike without losing your business. The higher the switching costs, the more a company can abuse you, because it knows that as bad as they’ve made things for you, you’d have to endure worse if you left.

Why is this happening?

Adding AI to a product strategy drives big increases in valuation, despite the fact that, many of the companies receiving big rounds from VCs have yet to deliver any revenue.

Even for established players, VCs are offering 4x, 6x or 10x valuation jumps year over year (or less). Similar trends are playing out for public companies embracing AI.

- Companies are incentivized to add AI…

- …so that they can say that have AI…

- …so they can collect the AI-sized check.

However, these companies are not yet accountable to ensure that what they have implemented is viable or useful to users.

The hype multiplier is real.

🤑

Eventually this will come out in the wash. Products that don’t provide real value will lose to those that do, and the market will consolidate.

But there will be a ton of debris leftover: UX debt, zombie legacy features, and crummy AI-driven (or written) content.

This will harm consumers. This will make the overall experience of the web worse, even as the wave recedes. We should be taking this seriously.

So, does it matter that an AI product serves a critical purpose?

The short answer is, no.

AI isn’t a monolith, and it’s not a solution; It’s a tool. Its use should be determined by the need or opportunity, and not the other way around.

There are certainly use cases where AI serves an essential need. It can help people do things they couldn’t do themselves, or help them save significant effort to get those jobs done.

On the other hand, some needs are less obvious, such as the need for fun, to spark curiosity, connect with others, or even waste time. Tools don’t need to have a specific commercial value (e.g. monetizable) to provide a good experience. They do need to provide enough of something that users are compelled to use it by choice.

I’m concerned with the uses that aren’t explicitly needful and that exist to serve the business at the expense of users. I would put LinkedIn’s functionality pretty squarely in this category.

So there’s a spectrum of use cases. As designers, product people, and researchers, we should be mindful of which we are working on at any moment, and adjust our approach to creating constraints, nudges, and incentives accordingly to ensure the experience centers on users and their needs.

Four categories of needfulness

1. Trap doors

When a product appears to exist primarily to serve some business need at the expense of users, these are trap doors. They may be connected to some incentive or feature that has the veneer of being user-centered, and some people may even find benefit from them. However, their central purpose is business need over user need.

- AI-prompted articles that serve as a clever SEO strategy, and are likely are helping the company train their eventual LLM, are not user-centered, even if users get “top contributor” badges for playing. People need to know the full experience they are opting into to truly evaluate – gamified incentives affect free will.

- Meta’s chatbot, which blatantly lays out in its terms that it will scrape user conversations for training data without any ability to opt-out, are not user centered, even if someone has an entertaining conversation with the AI (🤔 in fact, engaging conversations probably lead users to give more personal or revealing data to the AI).

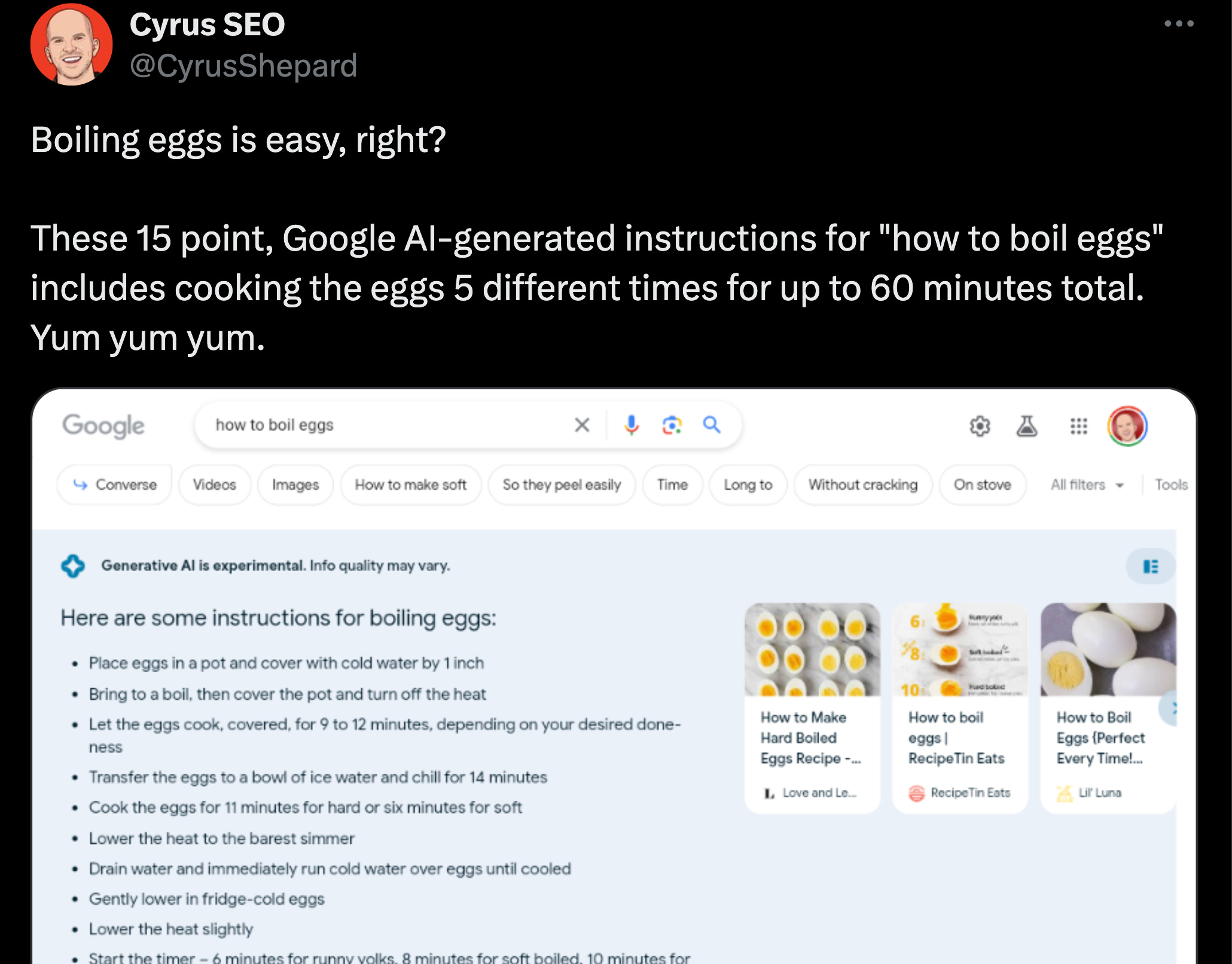

- Forcing Search Generative Experiences (SGE) on users who didn’t opt into them, is not user centered, even if some users do get to a good answer in the result. The justification by the most popular search engine in the world that a broad rollout is justified to “get feedback and learn how a more general population will find this technology helpful” is not sufficient, especially when it appears the results are clearly not ready for prime time.

Note: I recognize that unfortunately designers often don’t have the ability to choose what they work on. If you are unable to push back on dark patterns and incentives that are mandated by the business, you can still compensate with strong caveats and identifiers so users have full knowledge of what they are interacting with.

2. Vitamins

AI products or features can be simple, functional, or fun without serving a clear user need. Unlike “painkillers” (borrowing from the common product strategy framework), these are nice-to-haves, and therefore have a harder path to viability.

As with Trap Doors, the lack of viability means that businesses need to find other ways to derive value from them in order to justify the investment. Because Vitamins are often introduced in a marketing funnel or as a side-car experience tied to the brand, their value derives from web traffic, lower CACs, or increased conversion rates, making them less susceptible to dark patterns.

- Several of Ramp’s experiments incorporate AI, such as their mission statement generator. Each is connected to useful lessons about business operations, and while they are used for marketing purposes, their simplicity and their ability to function without personal information make them fairly benign.

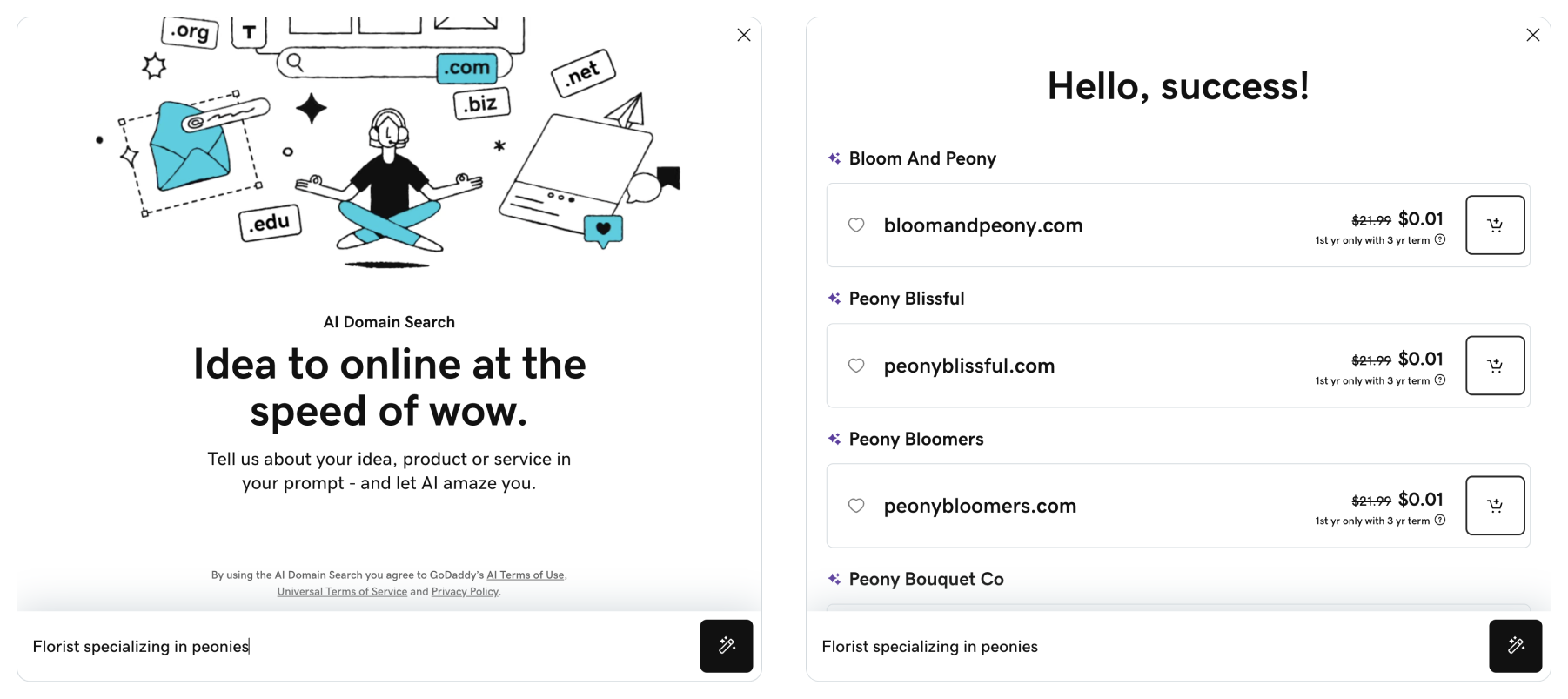

- GoDaddy’s AI Domain search and similar products essentially remove the step of manually searching for domains in your focus area. That’s a fairly small boost in efficiency, but it also helps educate users on how to find available domains by combining key words, and increases the likelihood of conversion.

- Automatic meme generators appear to be a new cottage industry, with fun tools like MemeCam and MemeDaddy popping up. I have no idea when I would need a tool that creates silly captions for random images, but I could totally see a company developing a fun tool like this to drive visitation.

3. Augmenters

One of AI’s superpowers is its ability to make mundane tasks feel lighter or easier. That’s where augmenters come in. These products clearly save users time or money, and they are willing to pay for the service.

- Perplexity.ai combines AI-generated summaries of search questions, combined with the resources that back up its response. Users can limit resources to more credible types, decreasing the effort it would take to conduct initial reviews.

- Github’s copilot has already demonstrated a sizable ROI through its ability to generate sample code and answer questions without requiring the developer to leave the IDE.

- Hypotenuse.ai combines a template library, easy-to-build prompts and other content tools with an automated SEO analyzer, combining multiple operations into one and making them faster to manage.

4. Access enablers

These uses of AI helps remove barriers and exclusionary experiences by compensating for capabilities that are inaccessible due to permanent, temporary, or situational circumstances. They serve a critical need by helping users complete tasks they are otherwise unable to perform, often in a multi-modal way.

- Zoom’s auto-generated captions allow all participants in a meeting to follow along regardless of their auditory capabilities at the moment.

- Automatic image descriptions allow users of Be My Eyes to upload an image and have the AI describe it, which can be read back using text-to-voice. Microsoft and Google have added similar capabilities to their bot development framework to make it simple for developers to auto-generated alt text when images are shared.

- AI-driven translation tools allow people to communicate more fluidly across languages, a fun addition to travel and critical for people who need to communicate accurately and urgently outside of their native tongue.

Considerations for different levels of needfulness

I’ve assembled a list of specific considerations and success criteria that you can use to evaluate your design of different types of AI Products.

These are intended to be a starting point, not exhaustive. Use them to prompt critical thinking and conversations with your team about building intentional experiences.